Women excel in several measures of verbal ability - pretty much all of them, except for verbal analogies.

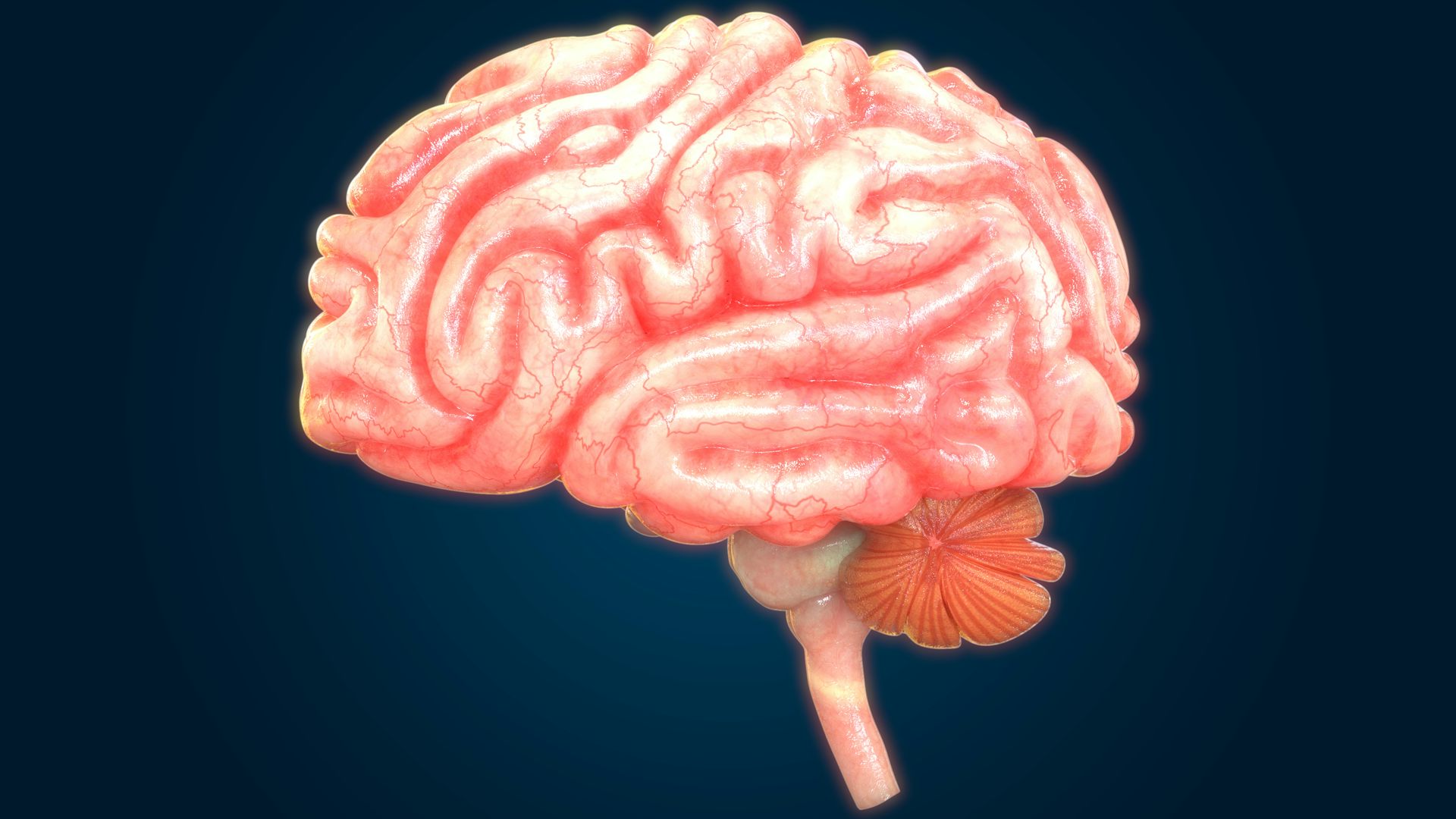

“These findings have all been replicated,” she says. Halpern and others have cataloged plenty of human behavioral differences. A much more recent study established that boys and girls 9 to 17 months old - an age when children show few if any signs of recognizing either their own or other children’s sex - nonetheless show marked differences in their preference for stereotypically male versus stereotypically female toys. It would be tough to argue that the monkeys’ parents bought them sex-typed toys or that simian society encourages its male offspring to play more with trucks. In a study of 34 rhesus monkeys, for example, males strongly preferred toys with wheels over plush toys, whereas females found plush toys likable. For one thing, the animal-research findings resonated with sex-based differences ascribed to people. Why? There was too much data pointing to the biological basis of sex-based cognitive differences to ignore, Halpern says. After reviewing a pile of journal articles that stood several feet high and numerous books and book chapters that dwarfed the stack of journal articles … I changed my mind.” In her preface to the first edition, Halpern wrote: “At the time, it seemed clear to me that any between-sex differences in thinking abilities were due to socialization practices, artifacts and mistakes in the research, and bias and prejudice. Social psychologists and sociologists pooh-poohed the notion of any fundamental cognitive differences between male and female humans, notes Halpern, a professor emerita of psychology at Claremont McKenna College. She found that the animal-research literature had been steadily accreting reports of sex-associated neuroanatomical and behavioral differences, but those studies were mainly gathering dust in university libraries. In 1991, just a few years before Shah launched his sex-differences research, Diane Halpern, PhD, past president of the American Psychological Association, began writing the first edition of her acclaimed academic text, Sex Differences in Cognitive Abilities. They counter, however, that data from animal research, cross-cultural surveys, natural experiments and brain-imaging studies demonstrate real, if not always earthshaking, brain differences, and that these differences may contribute to differences in behavior and cognition. Some researchers have grappled with charges of “neurosexism”: falling prey to stereotypes or being too quick to interpret human sex differences as biological rather than cultural. Our differences don’t mean one sex or the other is better or smarter or more deserving. Animal researchers, for their part, seldom even bothered to use female rodents in their experiments, figuring that the cyclical variations in their reproductive hormones would introduce confounding variability into the search for fundamental neurological insights.īut over the past 15 years or so, there’s been a sea change as new technologies have generated a growing pile of evidence that there are inherent differences in how men’s and women’s brains are wired and how they work. The neuroscience community had largely considered any observed sex-associated differences in cognition and behavior in humans to be due to the effects of cultural influences. His plan was to learn what he could about the activity of genes tied to behaviors that differ between the sexes, then use that knowledge to help identify the neuronal circuits - clusters of nerve cells in close communication with one another - underlying those behaviors.Īt the time, this was not a universally popular idea.

These circuits should differ depending on which sex you’re looking at.” “They’re innate rather than learned - at least in animals - so the circuitry involved ought to be developmentally hard-wired into the brain. “These behaviors are essential for survival and propagation,” says Shah, MD, PhD, now a Stanford professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences and of neurobiology. So, he zeroed in on sex-associated behavioral differences in mating, parenting and aggression. “I wanted to find and explore neural circuits that regulate specific behaviors,” says Shah, then a newly minted Caltech PhD who was beginning a postdoctoral fellowship at Columbia.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)